Farewell, Edmund White

An ambivalent appreciation of the pioneering gay-lib scribbler who has gone to the big bath-house in the sky

The American novelist, essayist, libertine and unashamed, unreformed gayist Edmund White has died this week, aged 85.

I first discovered him as a just-out, horny and rather gayist teenager in the early 1980s, reading his coming of age/coming out novel A Boy’s Own Story (1982), mostly for the filth, and his gay travelogue, States of Desire (1980), which toured the late 1970s, pre-Aids world of metropolitan American gay ghetto fabulousness, apparently while fellating a pocket thesaurus. (This is not necessarily a criticism.)

As I grew older, and less gayist - though still, of course, bumsex-obsessed - I developed a more ambivalent or perhaps oedipal relationship to his work and ‘brand’, which I touch on in the below review of his affectingly honest 2000 novel, A Married Man (and also here, in a tart review of his collected non-fiction).

Although entirely understandable for someone born in 1940, even if his mother hadn’t been a Christian Scientist and child psychologist who sent him to various shrinks to be 'cured', I found his ego-healing gay chauvinism, which Michel Foucault called ‘reverse discourse’ – and Gore Vidal dubbed ‘vulgar fag-ism’ – increasingly tiresome.

The ‘Gay is Good!’ slogan young Edmund picked up after happening to walk into the Stonewall Riots in 1969, and apparently wouldn’t or couldn’t put down for the rest of his life, had very diminishing returns - at least from my ungrateful, entitled, post-post-Stonewall point of view.

Nevertheless, he could certainly craft a sensual sentence. And I respected the way White stayed true to his gay libber roots at a personal level, refusing to clean up his slutty act and sing from the 'Same Love' hymn sheet in the assimilationist Noughties - even after getting gay-married in 2013, at the age of 73, to a chap 25 years younger than him (it was an openly 'open' marriage). And managing to publish yet another sex memoir last year, The Loves of My Life - at the ripe old age of 84.

All in all, it seems appropriate that he made his exit in flaming gay Pride June.

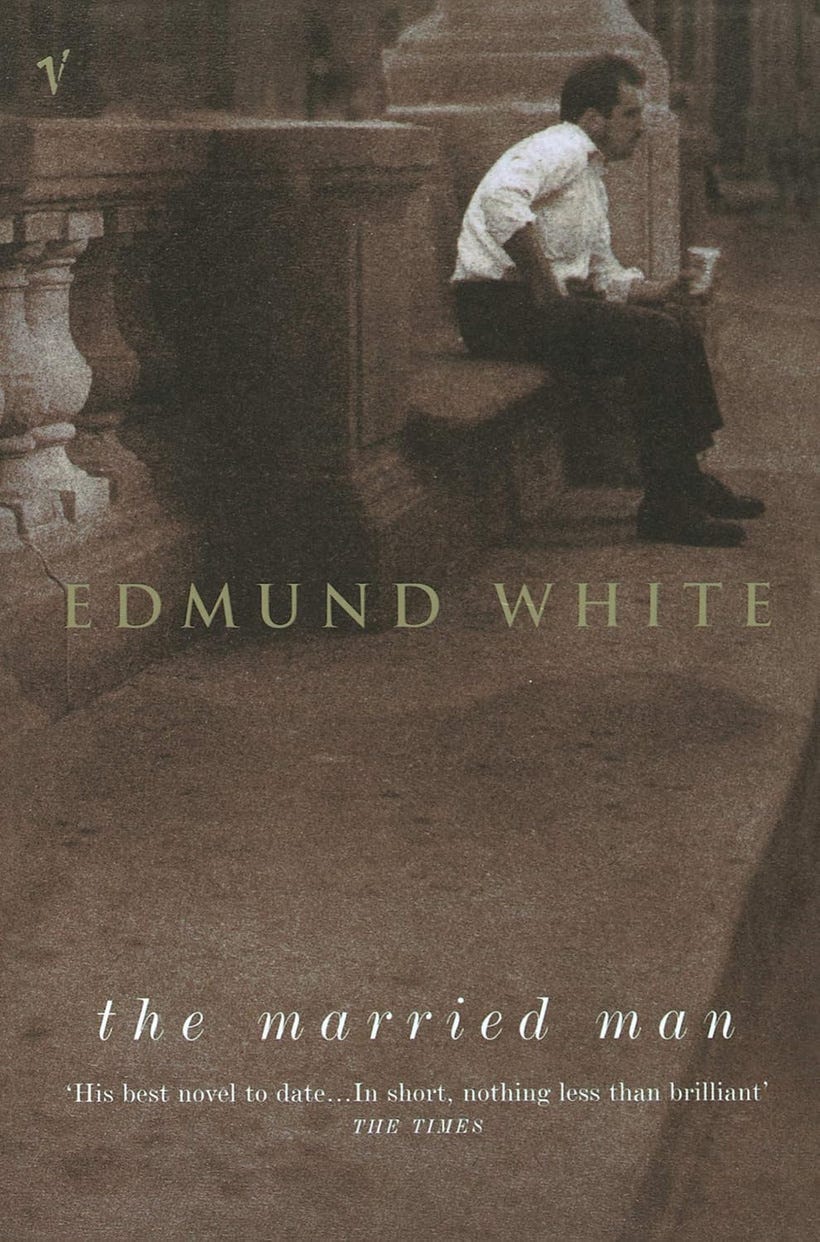

The Married Man, Edmund White

Reviewed by Mark Simpson (Independent on Sunday, March 2000)

“Please, if I should ever turn into Edmund White,” I begged a trusted friend shortly after reading White’s 1997 semi-autobiographical novel, The Farewell Symphony, “shoot me.”

It wasn’t that I didn’t rate his artistry. Anyone who can render twenty years of meaningless sex in the Parisian afternoon even more tedious than twenty years of meaningless sex in the Parisian afternoon actually is must be possessed of a great talent. Nor was it that I didn’t rate him as a person: I met him at a dinner party a few years ago and found him, like his prose, disarmingly charming and candid. No, it was the idea of Edmund White that I couldn’t bear.

I found it almost as unappealing as much of the serious book-reading public appeared to find it aspirational. After all, as ‘Austin’, the middle-aged American living in Paris with a snobbish disdain for Americans (who, like most of White’s protagonists bears more than a passing resemblance to White) puts it rather smugly: ‘Europeanised Americans are the best sort of people.’

Edmund White is a literary brand which promises salons, boulevards, and buggery in garlic-scented backrooms; a high-brow Anglo tourism of Gallic lowlife with plenty of disposable income and an indispensable sexual identity. George Orwell once complained that, to Americans, Paris represented a cross between a brothel and a museum. Plus ca change. For American and British fiction aficionados, White represents a cross between a bathhouse and a museum.

The jacket blurb to his new novel reads like an especially precious article from Conde Nast Traveller. It gushes about how Austin and Julien, a young architect, ‘dash between Bohemian suppers and glittering salons…’ and how their quest for ‘health and happiness drives them to Rome, to the shuttered squares of Venice, to Key West in the sun, Montreal in the snow and Providence in the rain – landscapes soaked with feeling which lead, in the end, to the bleak, baking sands of the Sahara.’

If only we could all arrange for the scenery to match our moods so tastefully!

Oddly, apart from the hint about a quest for ‘health and happiness’ and a cryptic ‘dark cloud on the horizon’, there is no mention that this is an AIDS novel. A slightly ironic ‘closetedness'. It’s a shame, because even though AIDS novels are hideously unfashionable these days, The Married Man is a good one – as AIDS novels go. Largely because it avoids the sentimentality and melodrama which drowns most of the others more fatally than pneumocystis pneumonia.

If The Farewell Symphony was a confession of sorts of a plague survivor’s guilty if entirely predictable and human irresponsibility (the protagonist has deliberately unsafe sex with a bisexual man after learning of his positive HIV status), The Married Man is an admission of a plague survivor’s guilty responsibility.

Set in the early Nineties, before the arrival of the protease inhibitor cavalry, The Married Man tells how an ageing but immature writer for glossy magazines abandons his life of selfish indolence to take on the crushingly heavy responsibility of caring for his terminally ill bisexual boyfriend – whose condition he may have brought about – not out of love but duty. It anatomises unflinchingly not only the progress of the disease which turns Julien into ‘a death’s head shaking on a stick’, but also his own ambivalence, self-delusion and questionable motivations. Its autobiographical nature is advertised by the fact that Julien's end parallels almost exactly that of ‘Brice’ at the end of The Farewell Symphony.

Perhaps corruption of the flesh and of the soul are handled so well here because White is an undisputed master of a slightly sickened-sickening sensuality – managing to evoke tastefully the distasteful truth of our own desire (and, mercifully, in The Married Man he appears to have finally mastered his habit of taking a sniff of self-justifying Seventies gay lib poppers every few pages). In one passage he describes a 24-year-old lad with ‘an intense stare and the strange smell of an old well, as though his fillings had started to rust in an excess of saliva.’ And later, Austin reminisces about ‘the hot, bitter taste of his anus, like stale cucumbers…’

Despite his tendency to never use one adjective when three will do, White can be very drole and to the point when he allows himself to be vulgar, especially in his observations of national foibles. Illustrating what he aptly describes as the ‘sing song complacency’ of the Dutch he recounts an experience in a Amsterdam bar where a ‘a lantern-jawed, gum-chewing blond with bad skin had asked him in a bored voice, “And would you like to be beat?” just as if he’d been saying, “And would you like more fries.”’

White was accused of being ‘self-obsessed’ by some when The Farewell Symphony was published. Part of the (self-obsessed) reason why I read The Married Man was to reassure myself I hadn’t turned into Edmund White in the intervening years. The answer I found within its unflinching pages surprised me – even if it was perhaps intended to.

No, I told myself, you haven’t turned into Edmund White. And you never will. You don’t have enough heart.