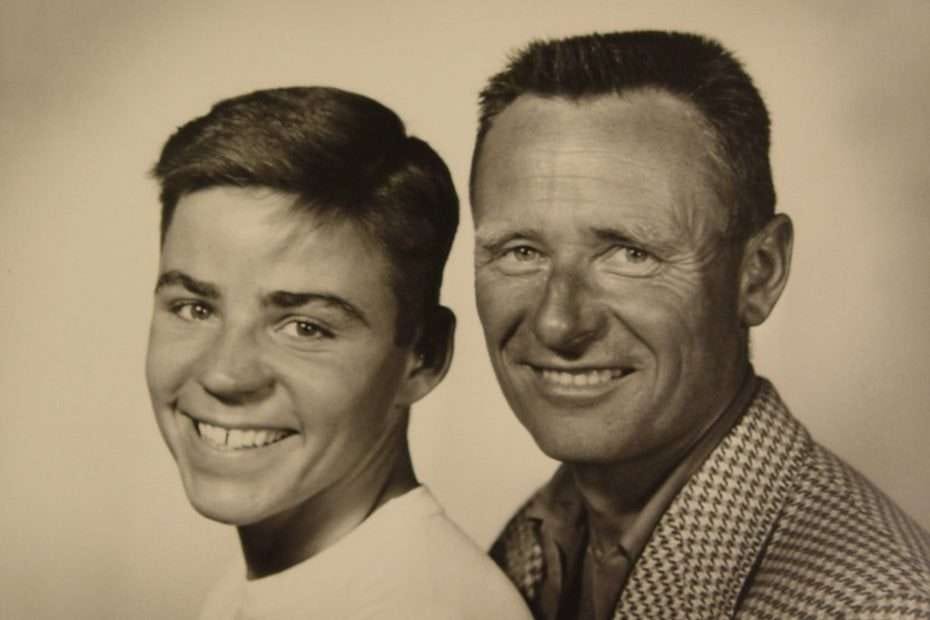

I just watched Chris and Don: A Love Story, on Amazon Prime Video, a 2008 documentary about Isherwood and Bachardy’s three-decades-long relationship, as told by a (then) still-boyish white-haired 74-year-old Bachardy, from their handsome hill-top home in Santa Monica, Los Angeles.

It made their love-affair more comprehensible than their idiosyncratic lo…