The Queerness of Clive James

The admirable total recall of a heterosexual memoirist

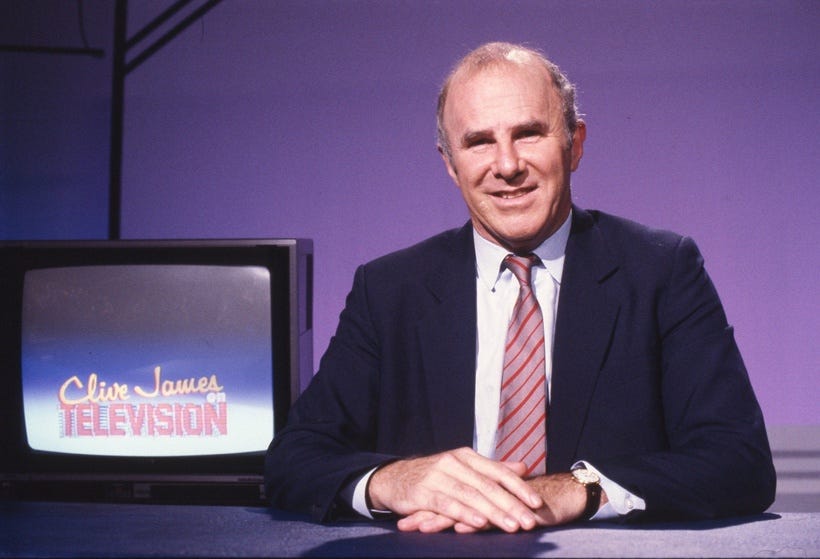

In November 2020, the writer and broadcaster Clive James finally signed off, aged 80, after a lengthy illness. James was much-loved in the UK, which he had made his home after emigrating from Australia in 1962 – and a wealth of obituaries were flourished. His lightly-worn wide reading, together with his sharply self-deprecating humour – and his passion for trash TV – endeared him to many Brits.

Though it did also earn him the disdain of other more ‘serious’ types back then who couldn’t bear the vulgarity of his early 1980-90s Saturday night TV shows. Or the vulgar fees they earned him. (Nowadays of course it’s difficult to imagine that any scribbler could end up with a prime-time TV show.)

There was also a melancholy behind his writing that I think the gloomy, gallows humoured British responded to. His father, imprisoned by the Japanese after the fall of in 1942 Singapore, survived being worked nearly to death as a slave labourer, only to be killed in a plane crash when being repatriated to Australia in 1945. James was just six years old.

Nevertheless, in all the write-ups and appreciations I saw there was, I felt, something missing. Something overlooked. The queerness of Clive.

And by that I don’t mean this heterosexually married family man’s appreciation of surface and his mastery of style. Nor do I mean to suggest that he was ‘non-binary’ - though he was born Vivian Leopold James, but was allowed to change his name because ‘after Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O'Hara the name became irrevocably a girl's name no matter how you spelled it’. (Gone With the Wind was released in the same year as his birth, 1939.)

No, I mean your actual genital queerness – about a time when James was in his own words ‘queer as a coot’. Though admittedly this time was a very long time ago – when James was adolescent. And his ‘queerness’ was always aiming for straightness.

James’ youthful same-sex mutual masturbation sessions and even love affairs were not uncommon in the pre-gay, mid-20th Century, especially in Australia with its convict origins and ‘mateship’ traditions, which I have written about rather too much (here and here). What was uncommon though was the way James lovingly documented that period or ‘phase’ as it would have been called (remember those?), in his 1980 memoir Unreliable Memoirs.

And instead of minimising and obscuring it as ‘experimentation’ as others might have done was quite insistent on using the ‘love’ word – as well as being very graphic about the groinal details.